|

Come and See the Natural Beauty of Jordan's "Lost City"

by

Amanda

Castleman

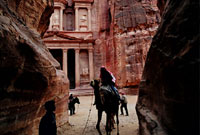

Hooves

tattoo down the Siq, a sinuous half-mile stretch of canyon.

Dusk drips down the walls. Gods squat in the shadows. Ancient

desert lords hacked into the scarlet sandstone. We cower to them, alone

and forsaken.

|

|

A man on as horse at Petra.

|

Tak-a-TAK,

tak-a-TAK, TAKKA, TAKKA, TAKKA-tak. Like typewriter keys, punched

hard in desperation, the hoof claps echo, cascade, and consume

all other sound. My life shrinks to this simple truth: nightfall

in a narrow rift. I am cornered in an alien and unfathomable

land. The beats signal danger. Takka-TAK.

The

rider charges past, leather coat tails aflap, silk neck scarf

tonguing the breeze. His hands grip the reins. His feet plant

solidly on the horse's saddle. "Oh my God," my friend

murmurs, clutching my dusty arm, "That's Indiana Jones!"

This

comment is high comedy, so near the grand cliff-shrine that

Harrison Ford theatrically toppled in The Last Crusade. We collapse

in giggles, two American women in the Middle East. Here despite

the nearby war. Despite the "honor" killings. Despite

the headscarves that we can't ever condone, however culturally

conscious or politically correct we grow.

Much

about this nation eludes us, and so it should. The Hashemite

Kingdom of Jordan is just 57 years old, but its history trails

back to the Bible — and beyond. This country boasts Lot's salty

spouse, the baptism pool of Christ and the mountain where Moses

first glimpsed the Promised Land. The first Islamic dynasty,

the Umayyads, built palaces beside the bayt shar, the goat-hair-tent

homes of their nomadic cousins.

|

|

Traditional

bagpipers perform in the restored Roman amphitheater at

Jarash

|

But

Petra, the country's archaeological diva, is an easy study.

The terrain — great swirls, lumps and crags of sunset-hued stone,

slicked by wind and water - has the piquant beauty of the Grand

Canyon. The Siq (pronounced "seek") snakes through

a half-mile massif that towers 250 feet high. Its mouth kisses

the Pharaoh's Treasury, the Khaznat Far'oun, a glorious confusion

of East and West, deservedly one of the world's most famous

facades.

The ancient Arabs etched buildings into the chasm beyond. Greco-Romanesque columns chipped out here, a Christian monastery there, tombs everywhere. This oasis once housed 30,000 people, though only six inches of rain fell each year. They grew rich, catering to the spice and silk caravans crossing the vast, kitty litter-like grit of the Syrian Desert.

Petra is intoxicating: art and natural beauty wrought wide-screen…with all the spiritual wallop of Sedona or Stonehenge. But its genius is in the Bedouin. The Bdul still swarm over their ancestral home. They peddle camel rides and coffee laced with cardamom. They shout and sing and sell trinkets under embroidered canopies.

Cook fires blacken crannies in the rock. Goats graze in the scrubby slopes, studded with cacti and cedar trees. Footsteps crush eggshell-shards of Nabataean pottery, fired over 2,300 years ago during the Semitic empire's heyday.

|

UNESCO evicted the Bdul from Petra in 1985. They work at the site now, , but sleep in a nearby village. |

The women inscribe inky kohl around their eyes, dipping silver toothpicks into camel-bone compacts. The men knot their turbans - the red-checked Jordanian kaffiyeh -tight against the gorge's gusts. Children race donkeys up and down the snaggle-toothed scarlet amphitheater.

"They are the preservers of knowledge, of birds, of animals, of flash floods," points out Patricia Bikai, an American archaeologist who studies Petra. "They grew up in tents there. They know more about my excavation than I do."

UNESCO evicted these Bedouin in 1985, when it designated the park as a world heritage site. No more children would be born in Nabataean tombs under the gaze of the goddess Hayyan.

Squeezed into Umm Seyhoun, a modern village, they resent the concrete cubicles. Home by day, displaced by night, the Bdul time-share their past. Discarded mattresses and snarls of blankets show that many sneak back to sleep. Petra sprawls over 400 square acres, so disappearing is as easy as stepping in camel dung.

In fact, the city itself was lost once. Earthquakes destroyed the desert stronghold in 393. Sand smothered its bones. By the 13th century, only the Bedouin remembered these caves and their poetic depths. A Swiss explorer, Jean Louis Burckhardt, wandered here in 1812, unearthing the "rose-red city half as old as time," as the theologian John William Burgon famously dubbed it.

An Arab proverb stresses: "for every glance behind us, we have to look twice to the future." Petra's future involves a $5.6 million Swan-style visitors' center makeover in 2006. Pine and olive seedlings will sprout into shady groves, binding the sifting desert soil. Its guardians will recycle wastewater, thanks to a $27m scheme, aided by the World Bank. Limited access, for tourists and Bedouin alike, will preserve Petra's marvels, but at a price. This site, so vital, may slip into a dusky half-life.

Jordan has many other delights: the briny Dead Sea and its salt encrustations, Crusader forts, the indigo Gulf of Aqaba, and the city of Madaba's elaborate mosaics. See the slender oryx, white Arabian antelopes, that have been rescued from extinction, tribal pipes wailing in the Roman amphitheater at Jarash, and backgammon battles in cafes and great spice sacks in Amman's outdoor market, the suq. See the moonscape of Wadi Rum, which T.E. Lawrence dubbed "vast, echoing and God-like".

One scene frames the Hashemite Kingdom: a moment in the Siq, poised between stone and sky, dark and light, awe and laughter.

The ruins are dead. Long live the ruins.

If You Go...

Petra

Jordan Tourism Board

P.O. Box 830688

Amman, Jordan 11183

Phone : + 962 6 5678444

e-mail

|