|

Take a Tour Around Lively Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

words and

photos by Wendy O'Dea

|

|

A

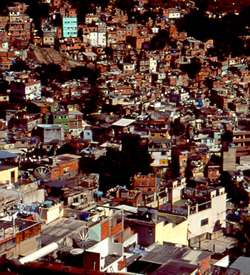

fevala of Rio de Janeiro.

|

Rio

is full of surprises.

I knew what most people know about this city: it's full

of long, beautiful beaches with sun worshippers in tiny swimsuits; the people

are vibrant and beautiful; and the city knows how to throw a serious party about

this time each year, Rio's infamous Carnevale. I

didn't know that in Rio I could find some of the best sushi I've ever eaten, soar

through the air in a city that is one of the world's best for hang gliding, and

stroll through run-down slums - mini cities within the city that house a subculture

that is both frightening and fascinating.

I

discovered all this and more on a recent trip to Brazil that was prompted both

by my curiosity and pocketbook. With the economies of most South American countries

tanking for a number of years, the dollar just keeps getting stronger. I envisioned

myself lounging at little kiosks along Copacabana beach drinking caiparinhas,

the refreshing Brazilian cocktail made with sugar cane alcohol, then dancing the

Samba into the night with a tall, dark and handsome Brazilian. That last part

alone pretty much made the decision a no-brainer. However,

the drive from the airport, about 13 miles from the center of Rio, was eye opening,

revealing a metropolis both magical and monstrous. Along with the anticipated

views of Sugar Loaf Mountain and Christ the Redeemer jutting skyward in the distance,

there were unexpected views of the numerous favelas, or city slums, cascading

down the sides of picturesque hillsides. I

knew Brazil's crime rate gave it a bit of dicey reputation, but I knew nothing

of the large number of urban slums that dot the landscape. I hadn't yet seen the

art house film Ciudad de Deus (City of God), which is set in these drug-ridden

slums, but soon after bombarding my driver with questions, learned of an unusual

tour taking visitors inside these poor Brazilian communities.

I'd

intentionally traveled in September to avoid the chaos

of Carnevale. I wanted to see the real Rio. Now that

I was, I saw my caiparinha-sipping vacation quickly

morphing into an educational experience of learning

how nearly 1.5 million people - Rio's "other

half" - live.

Intrigued by what I saw, I wasted no time contacting Favela Tour, the organization that coordinates visits to these areas. The day after my arrival, our middle-aged guide, Luis, picked up a friend and me from Copacabana Beach where we were staying at the high-end J.W. Marriott. He drove us to Rocinha (pronounced Ro-seen-ya), Brazil's largest and most complex favela. A population of over 150,000 people live in an area approximately one square mile with dilapidated shelters piled one upon the other, constructed of old scraps found by residents and giving new meaning to the phrase "brick by brick."

Driving toward Rocinha up the steep hillsides near Two Brother's Mountain, the contrast of the have and have-nots is striking. Large expensive homes and the private American school are located near the corner of the last hairpin turn before entering Rocinha. Thereafter the smell of trash and exhaust begin to fill the air.

|

Rio's Rocinha favela. |

As we drove through the narrow alleys and maze of streets in Rocinha, Luis began to enlighten us about these slums and how they operate. Many of the 600 favelas in Rio de Janeiro began with a few squatters who built makeshift shanties. When the government failed to disband them, they continued to grow into the expansive ghetto communities they are today.

"These shanty towns had no infrastructure, no services," Luis said. "No water, no sewage, no power. The government believed that without these services, these communities couldn't survive."

But they were proven wrong and by the time the government recognized that the favelas were not going to disband on their own, it was too late to relocate the hundreds of thousands living in them across Rio.

"We want to show the outside world why people live like this, how they came to live like this and how they survive in adverse conditions," Luis continued, referring to himself and Marcelo Armstrong who created and runs most of the favela tours in Rio. Armstrong, fluent in English, Italian, French, Spanish and Portuguese, has developed close relationships with people within both Rocinha and a smaller favela nearby, Villa Canoas.

"You're completely safe when you're in a favela," he told our tour, which included a young Scottish couple, my friend and me. "The violence that takes part in the favelas is not directed at tourists. You can bring your most expensive camera with you and no one will bother you."

He was right. I dragged along about $1,500 worth of equipment and did not feel threatened. Had I not been with Luis I would have felt anxious and in danger but he knew his way around and seemed to have a good relationship with residents, smoothly moving from point A to point B without attracting unnecessary attention. Admittedly, it did feel somewhat voyeuristic, but most people went about their daily business - hanging laundry, shopping at the daily street markets - paying little attention to the foreigners slipping in and out of their midst.

About the same time Marcelo was starting his tours of the favelas, a $300 million grant from a variety of international banks was approved for Rio's municipal government to create the Favela-Bairro project, a program to transform these troubled areas into functioning neighborhoods.

The Favela-Bairro program's main goal is to integrate existing favelas into the city through improvements in public services, social policies and infrastructure. The program provides money for building community and recreational centers, job training, city-provided sanitation services and opportunities to legalize land tenure, giving those once considered squatters an opportunity to own their homes and use them as collateral for loans to start legitimate businesses.

One favela that has greatly benefited from the Favela-Bairro project is Villa Canoas, the second stop on our tour. We learned that part of the $20-25 (depending on the exchange rate) we were paying for this half-day excursion was helping to sponsor the school at Villa Canoas. The Italian Rotary and government of Rio de Janeiro provide the remaining two thirds of operating costs.

|

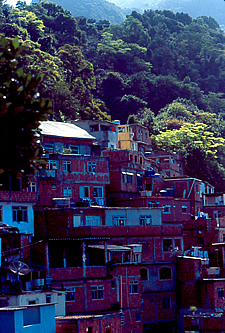

One of Rio's favelas. |

This small community of approximately 2,000 residents is clean and orderly. There is a library, medical center and a small computer room with five terminals that is providing computer training to young residents. Since its residents have been able to secure loans, small cafes, restaurants and grocery stores have popped up with one well-regarded restaurant located on the outside corner of the favela.

"I brought a tour by this corner not long ago," Luis told us, "and there was a long line of police at the intersection. Concerned, I slowed down to inquire if there was a problem and the policeman told me there was no problem - they just really liked the food!"

Luis' enthusiasm for his subject makes all the difference on a tour like this. It's clear that he's proud to see Villa Canoas developing a good reputation. The tour itself has the potential to feel like a display at a zoo with visitors looking down their noses, but this feels more like visiting a living museum and an opportunity to see a city evolve.

Although it will take decades to transform all of these ramshackle, disparate neighborhoods into functioning communities with residents who feel empowered to make better lives for themselves, it's clear they are building it… brick by brick. I'll raise my Caiparinha to that. (...BACK)

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Favela Tour: Marcelo Armstrong

www.favelatour.com.br

JW Marriott Hotel Rio de Janeiro

Avenida Atlantica, 2600, Copacabana

Rio de Janeiro, 22041--001 Brazil

www.marriott.com |